In 2015, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) celebrated its 20th anniversary, coinciding with the 50 years of pharmaceutical regulation in the European Union (EU). In the EU, pharmaceuticals are legislated at the EU level, but the enforcement of this legislation is typically left to the Member States. Yet also in this area we can see a trend of verticalization. This development has resulted in too complex procedures, with potential negative effects on accountability.

The creation of an EU sanctioning power

Generally, enforcement in EU pharmaceutical regulation is quite traditional with indirect administration as a core principle: enforcement largely remains in the hands of the Member States.

Regulation 726/2004 governs the centralized marketing authorization on the EU level. Directive 2001/83, i.a. deals with national marketing authorizations. Yet, both oblige the Member States to set up a system to supervise companies’ compliance with the legal framework. The role of the EMA is then limited to coordinating and gathering information on the inspections carried out by the national competent authorities but it does not have inspection powers itself. When it comes to sanctioning companies, this was exclusively done by the Member States.

With regard to sanctioning powers, the traditional enforcement structures were shaken up by the adoption of the Penalties Regulation in 2007. The regulation empowers the EMA – also on request of the Commission or Member States – to initiate a so-called ‘infringement procedure’, which can lead to the Commission adopting a fine of up to 5% of the annual turnover of the company concerned. This EU sanctioning power was deemed necessary in order to ensure that infringements of obligations linked to a centralized marketing authorization are properly sanctioned, instead of being confined to only having the option to change or withdraw the marketing authorization of a product. However, the EU fine can be applied in parallel with national fines, which, if used, will raise evident issues related to the ne bis in idem principle.

Complex Verticalization: the Urgent Union Procedure

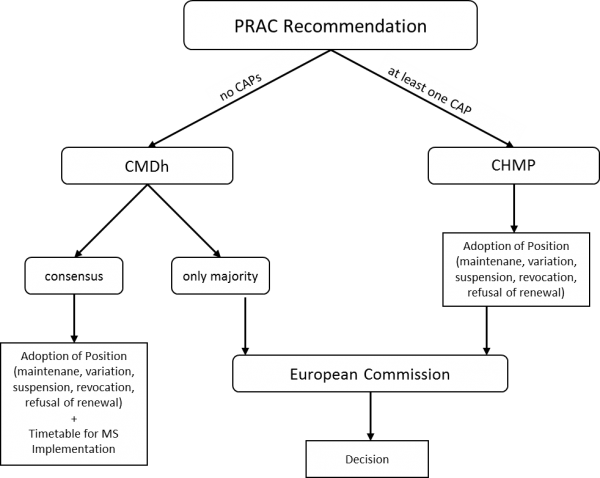

The Urgent Union Procedure is the most recent example of the ongoing verticalization (Articles 107i-107k of Directive 2001/83). This procedure can be initiated by any Member State or the Commission, where safety concerns arise e.g. because of adverse reactions to a medicine. The procedure is applicable regardless whether the marketing authorization is granted at EU or national level. The only exception is when a product is authorized only in one Member State. That MS will then have to deal with the matter. Once the procedure has been started, EMA’s Committee responsible for pharmacovigilance (PRAC) will assess the safety concerns. The PRAC will assess data on adverse drug reactions from the EMA and the national authorities. It will then recommend measures such as withdrawing the marketing authorisation or risk minimisation measures such as no longer using the medicine for certain groups of patients. The recommendations of the PRAC can then either go to the Coordination Group for Mutual Recognition and Decentralized Procedure (CMDh) or the CHMP, which is the main scientific committee of the EMA. The CMDh is not a formal part of the EMA but a group where national medicines agencies’ representatives meet to discuss. This means that not the EMA but the national authorities will be accountable for CMDh decisions. However, as they are acting collectively in the CMDh, this creates accountability gaps as no collective accountability exists.

Where exactly the safety issues will be dealt with – the CMDh or the CHMP – depends on where the product or group of products subject to the Urgent Union Procedure is authorised. If only nationally authorised products are concerned, the Coordination Group will decide on how to proceed with the products in question and the decision of the CMDh will then be executed through measures in the Member States. However, where the CMDh fails to reach the required consensus the Commission will adopt a decision, which will then have to be executed by the Member States. This has, for example, happened with the contraceptive Diane35. This clearly changes the remedies available to a company concerned. ‘Consensus’ decisions of the CMDh are arguably not challengeable before the EU courts, while a Commission decision is. In the first case, a company concerned would have to initiate parallel procedures in several Member States.

Moreover, as soon as one concerned product is centrally authorized, the CHMP will form an opinion on the matter and the final decision on actions, such as withdrawing the marketing authorisation, will be taken by the Commission. In that case, the Commission will adopt a decision for the centrally authorized product and also instruct the national authorities on how to proceed for nationally authorized products.

Overall, this procedure is highly complex and the question who will take the final decision is subject to arbitrariness with regard to the product concerned and the place of its marketing authorization, as well as with regard to whether or not the CMDh can achieve consensus. This regime opens the possibility for the EU to take an enforcement measure against a product that is originally authorized by the Member States. This is a prime example of how enforcement is not the exclusive domain of the national authorities anymore.

Verticalization challenges accountability!

The verticalization of pharmaceutical regulation as described in this blog post has certainly augmented the procedural complexity of the described enforcement procedures. This is problematic: the short presentation of the procedures already shows that because of their complexity they are not a hallmark in transparency. When the Penalties Regulations will be applied, the parallel sanctioning at EU and Member State level will furthermore raise questions related to the ne bis in idem principle.

The verticalization of enforcement tasks will also lead to challenges with regard to the legal and political accountability of the EMA. Already the general accountability regime applicable to the EMA is not fully coherent and begs the question whether the accountability regime should not be refined. When and if further enforcement powers will be vested in EMA, such a refinement could consist in adding specific accountability mechanisms for the EMA’s enforcement activities. Moreover, the above noted composite procedures should be embedded in a sound procedural framework which in turn would strengthen accountability and ensure relevant safeguards for the parties concerned.