By Arailym, Patrick and Sondra

The road to what might be called regulatory maturity is often a long one. In EU cybersecurity regulation, a culture of vertical and horizontal collaboration is optimistic but seemingly ineffective. It likely leaves the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) feeling somewhat envious of the centralised enforcement powers recently vested in the Anti-Money Laundering Authority (AMLA). How feasible would it be for ENISA to follow in AMLA’s footsteps? This blog post examines whether there is regulatory space, or even a solid legal basis for such an evolution. Due to the differing contexts of financial crime prevention and cybersecurity, the limits of an analogy between the trajectories of the two agencies will become clear.

What is ENISA?

ENISA – the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, previously known as the European Network and Information Security Agency, was established in 2004 by Regulation No 460/2004. It was reformed by Regulation No 526/2013, which was later repealed by the Cybersecurity Act.

ENISA – the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, previously known as the European Network and Information Security Agency, was established in 2004 by Regulation No 460/2004. It was reformed by Regulation No 526/2013, which was later repealed by the Cybersecurity Act.

The Cybersecurity Act granted ENISA a permanent mandate along with increased responsibilities, transforming it from a “Cinderella” agency into a key cybersecurity entity in the EU. ENISA aims to achieve a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union. Its main tasks include:

- Supporting EU legislation implementation and the development of EU-wide cybersecurity standards

- Enhancing operational cooperation and coordination among Member States, Union institutions and private sector actors

- Managing cybersecurity certification schemes to increase trust in information and communication technology (ICT)

Photo credits: ENISA website

The Emergence of AMLA

The evolution of the EU’s anti-money laundering framework has seen notable advancements, starting from the initial anti-money laundering Directive (AMLD1) in 1990 to the latest updates with AMLD6, Anti-Money Laundering Regulation (AMLR), and Anti-Money Laundering Authority Regulation (AMLAR). This development signifies an expanding regulatory focus that originally targeted drug trafficking in the 1990s, evolving into a robust framework that addresses intricate financial crimes like cyber-enabled money laundering. A significant shift occurred with AMLD3, which embraced risk-based approaches for customer due diligence (CDD). The enactment of AMLD4 improved transparency by creating mandatory central registers for beneficial ownership information, a refinement further augmented by AMLD5 (2018), which required public accessibility. The recent introductions of AMLR, AMLAR, and AMLD6 establish centralised oversight while adapting to technological advancements by creating a unified supervisory body across the EU, effectively standardising anti-money laundering initiatives among member states and confronting new technological hurdles. This evolution exemplifies direct enforcement and is a new form of functional spillover that arises from internal pressure and functional necessity, rather than from external crises. This indicates that achieving the established policy goals necessitates the expansion and uniform application of EU law. Below, we delve into why and how direct enforcement is essential for ENISA to attain a high common level of cybersecurity throughout the EU.

Why should ENISA follow the same trajectory as AMLA?

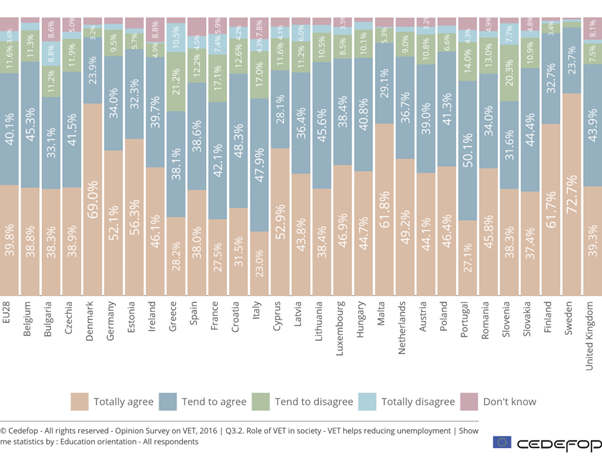

The increasing frequency and sophistication of cyber threats pose significant risks to economic activities, public services, and citizens’ privacy. In recent years, the EU has implemented several legislation addressing cybersecurity, such as the Cybersecurity Act, NIS 2 Directive, Cyber Resilience Act, and Cyber Solidarity Act.

These legislations have expanded ENISA’s capacities, but they are insufficient for the EU’s ambition to enhance cybersecurity across the Union, as the success of EU cybersecurity policies relies on implementation by Member States. For example, the NIS 2 Directive has so far been transposed by only four Member States, prompting the European Commission to open infringement proceedings against 23 Member States. This presents a real risk of fragmentation across the EU, which hinders effective cybersecurity. From a functional spillover perspective, the increasing cybersecurity threats and divergent approaches among Member States suggest that ENISA’s role may need to evolve beyond its original advisory and coordinative function towards enforcement powers.

The situation facing ENISA mirrors AMLA’s earlier context – both agencies emerged in response to fragmented national practices and cross-border threats that require unified, robust responses. However, while AMLA was granted limited enforcement powers due to the ineffectiveness of the previous decentralised approach and the lack of cooperation among national AML/CFT supervisors, ENISA remains confined to coordination and advisory functions. To some extent, one could argue that ENISA’s case resembles AMLA, and granting ENISA enforcement powers would ensure compliance with EU cybersecurity standards and achieve a high common level of cybersecurity across the Union.

However, this might be an impossible mission or one that lies in the fairly distant future… Direct enforcement for the wandering ENISA faces a steep climb, blocked by the EU’s limited competences in security matters, an area still fiercely guarded by the Member States.

How this trajectory can be beneficial

As referred to above, the sole competence of Member States in matters of public and national security (recognised under Article 4(2) TEU) currently limits ENISA’s ability to gain direct enforcement powers; there is, however, precedent for derogation from the national security exemption, as can be observed in the Privacy International case (paragraph 44) in relation to the e-privacy Directive.

For now though, we must not jump ahead but instead envisage some preliminary steps that may take ENISA some distance down AMLA’s beaten path. A prerequisite of any centralisation is an unequivocal delineation of the agency’s role in a crowded regulatory environment. The elaboration of the EU cybersecurity landscape in recent years has led to a blurring of the lines between the competences of the entities involved, particularly with the emergence of several networks and centres at the EU level aiming to prepare for, respond to, or analyse cybersecurity threats and incidents. Although the notion of collaboration seems to be favoured in EU cybersecurity policy, the lack of exclusive specialisation on ENISA’s part would undermine any future enforcement remit for the agency. Thus, policymakers should pinpoint the tasks and responsibilities the execution of which would allow ENISA to contribute most optimally to the improvement of EU cybersecurity. This prioritisation of tasks would enable ENISA to enhance its operational efficiency, and ultimately its reputation, potentially paving the way for a transition to a more substantively empowered role.

|

|

ENISA |

AMLA |

|

Legal basis |

Cybersecurity Act (2019) & NIS2 Directive |

AML/CFT Regulation (2024) & AMLD6 |

|

Enforcement powers |

No direct enforcement (supports national authorities) |

Direct enforcement (40+ high-risk financial entities (crypto, cross-border institutions)) |

|

Sector focus |

All critical sectors (energy, health, transport, digital infra) |

Financial sector priority, limited non-financial oversight |

|

Enforcement tools |

Technical enforcement i.e., cybersecurity certification, Vulnerability reporting; Operational Tools i.e., Cyber Exercise Platform for crisis simulations, CSIRT Network coordination; Compliance Leverage i.e., National strategy evaluation toolkit Biennial risk trend reports to EU institutions |

Corrective measures i.e., operations restrictions, government structures; Financial sanction i.e., fines; Investigative powers. |

|

Dispute resolution |

Non-binding recommendations through Cooperation Group |

Binding arbitration in cross-border supervisory conflicts |

During the

During the  www.wordsandquotes.com

www.wordsandquotes.com

ETIAS, THE ELECTRONIC TRAVEL AUTHORISATION FOR EUROPE

ETIAS, THE ELECTRONIC TRAVEL AUTHORISATION FOR EUROPE