By Danielle & Lisette

The European Commission has adopted a ‘new aviation strategy’, a milestone initiative to boost Europe’s economy, strengthen its industrial base and contribute to EU global leadership. This will not only benefit businesses, but also European citizens by offering more connections to the rest of the world at lower prices.

This new Aviation Strategy is an initiative listed in the Commission Work Programme of 2015, which consists of a Commission Proposal for a revision of Regulation 216/2008 on establishing the European Aviation Safety Agency, the so-called ‘aviation-package’. The goal is to adjust and adapt the EU regulatory system to new safety threats and new challenges. The Strategy aims to improve the flexibility, proportionality and efficiency of the system and it should optimise the use of the available resources at Union level. This revision entails major influences and consequences on the already established framework of EASA.

EASA was established in 2002 in order to provide for better arrangements in all fields covered by Regulation 216/2008. The main purpose for establishment was to enable one expert body at EU level to carry out certain tasks relating to aviation safety. EASA has many different tasks in three main areas: the strategy and safety management, the certification of aviation products and the oversight of approved organisations and the EU Member States. The latter area is related to the enforcement of EU law, which needs to ensure that the EU Aviation Safety rules are applied correctly and uniformly throughout the Member States. However, when enforcement powers are granted, the need for accountability becomes relevant. Accountability is concerned with ex post oversight, with ascertaining after the fact, to which extent the Agency has lived up to its ex ante mandate and has acted within its zone of discretion (Busuioc 2007, p. 10).

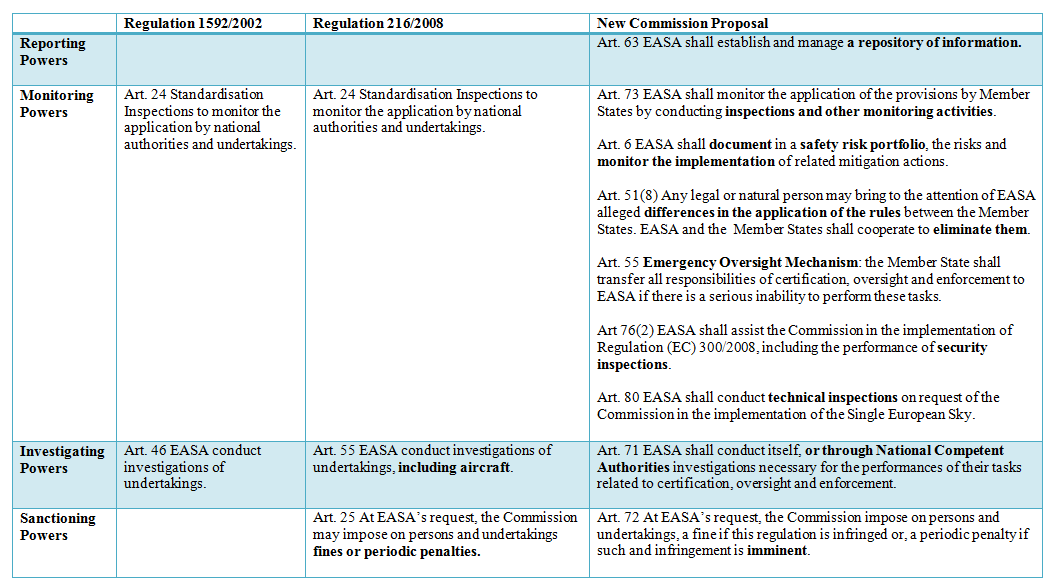

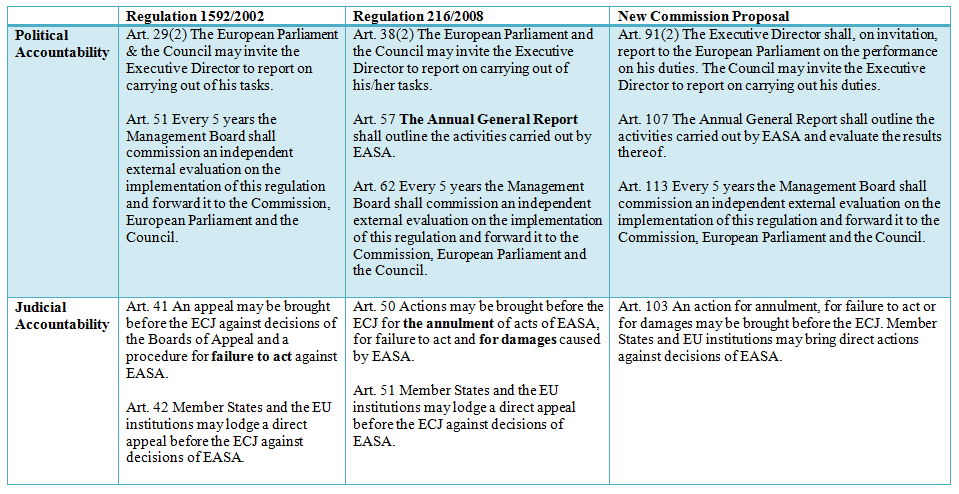

The revision of Regulation 216/2008 is not the first one in time (previously, Regulation 1592/2002 on the establishment of EASA has been repealed by Regulation 216/2008). This repeal increased the number of different enforcement powers of EASA, which will be only more if the Commission’s Proposal will be adopted. And thus, we tried to find a link between this enlargement of enforcement powers and the degree of political and judicial control over the Agency. Both tables below show the differences between the two regulations and the Commission’s Proposal regarding enforcement powers and control instruments to hold EASA accountable.

It becomes clear immediately that the enforcement powers increased over time, in particular when the Commission’s Proposal for the revision of Regulation 216/2008 is adopted. However, as we can see hardly anything changed regarding control. The only noticeable difference was the introduction of adopting an Annual General Report of the activities and their results by EASA each year. Thus, with no extended control provisions as a reaction to the increased competences, we can say that there is a great imbalance and call this a serious accountability deficit.

This is not the only problem we encountered in our research, which lead us to further research the effectivity of the controlling instruments, in particular the ‘newly’ introduced Annual General Reports. The first Report was published in December 2008. However on enforcement this Report only listed the countries where they conducted standardisation inspections and the Report only mentioned the investigation into the British Airways Boeing 777 accident in London in early 2008. The report does not mention anything about the results of the standardisation inspections and investigations, sanctions are not mentioned either. The same counts for the year 2009, where EASA did not even take the time to list the countries where standardisation inspections were carried out, it were just 85 visits. Since 2010 the Annual General Report included more information on the standardisation inspections: 111 inspections, raised 949 findings from which 876 findings were classified as non-compliances. Approximately 20% of these findings were classified as significant deficiencies that may raise safety concerns. This way of reporting on standardisation inspections is still continuing this year: no information is given about the consequences or sanctioning of the non-compliances and no detailed information is given about other investigations. The reason of inadequate reporting could be “silence of agencies’ founding acts about information expected to be in the annual reports” and the absence of interested readers (the European Parliament and the Council), who would demand justifications and explanations of the ‘naked’ numbers provided. At this moment ‘you get what you ask for’ (Scholten 2014, p. 106-110).

In the end we can conclude that EASA has far reaching powers to ensure that EU law on Aviation Safety is applied in compliance with EU law and uniformly throughout the Member States. If the Commission Proposal was adopted, that powers would increase. However, since enforcement competences and accountability are linked, an increase of powers should imply an increase (or modification) of existing controls, by e.g., making accountability (reporting) obligations more specific. As derives from this brief analysis, we can say that, in our opinion, there is a serious lack of control over EASA’s competences and activities and the control established earlier cannot be called effective.