By Agata, Alexander, Mario and Patrik

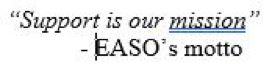

The European Asylum System revealed many issues and weak spots especially under current migratory pressure. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) is a European Union (EU) agency which struggles to practically guarantee the effective protection of asylum seekers, due to its limited de jure powers. EASO managed to develop steadily throughout the years (Figure 1) and it is presently responsible for the support and implementation of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). This blogpost suggests an approach towards improving EASO’s operation framework and exploring a possible further extension of its current powers.

EASO in Law (de jure) and in Action (de facto): one framework, two different agencies?

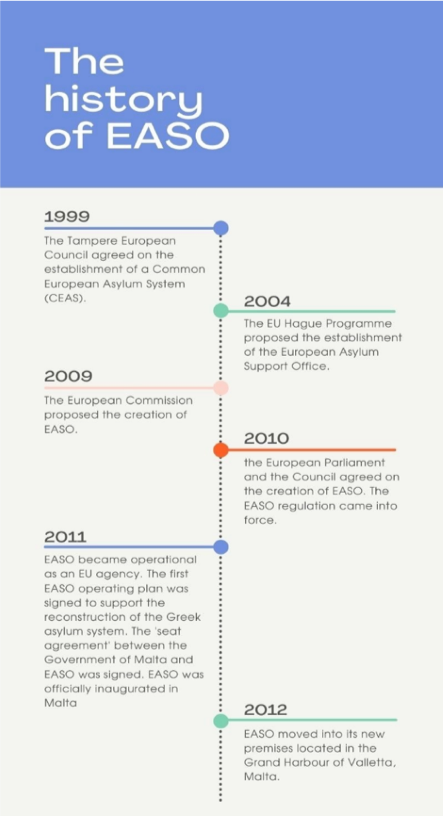

The current legal framework suggests that EASO’s powers can be divided into two sections – advisory and supportive (Figure 2). In terms of operational support, in collaboration with MS (at least) two types of plans can be seen, the main ones being the ‘supportive-advisory’ and the ‘action plans’. These plans set out a variety of activities.

Even a glance at the performance of EASO in different Member States (MS) can help us identify some of the most basic issues involved and negatively impacting its operational framework and assisting process.

Firstly, EASO’s corresponding bodies in the MS—i.e the national bodies/agencies that are responcible for carring out or assisting with the implementation of its mandate; ex. Asylum Services in Greece and Cyprus—are being ‘pushed around’ by central governmental executive authorities that aim to promote their politicized agendas, effectively cutting the agency’s voice. This means that, whenever decisions need to be taken, due to its mandate, EASO is only able to play its advisory statutory role, while the final decisions on key policies are adopted unilaterally by the various responsible ministries (central government). An example where this practice becomes apparent is Cyprus, having adopted a more centralized control system on migration (i.e. the ministry has given significant, almost exclusive powers to decide on migration issues, while the corresponding asylum-related bodies and agencies play a purely executive role). The corresponding voices of the national bodies of EASO are thus being translated in background noise impacting the agency’s overall value as an advisory agency, and, therefore, its efficiency to implement its supportive and advisory mandate. In other words, the existing mandate of the agency is not enough to impact real change on asylum-related matters, since even when it raises its voice state specific interests and policies come into play to silence it. Overall, in reference to general enforcement issues, EASO remains a toothless tiger.

Secondly, even when EASO and its corresponding bodies proceed on undertaking further, more action-related steps, the agency does so by overstepping its operational powers, gaining indirect decision-making ones. For example, in Greece the agency shifted its competence from “purely expert consulting” to “undertaking interviews with asylum seekers and submitting recommendations that are followed and formally endorsed by domestic authorities” (Nicolosi and Rojo), thus showing a huge lack of accountability. In other words, it seems like it is willing to “sacrifice accountability for effectiveness”. This can be considered as the main problem with EASO. However, despite accountability issues, further generalised problems relating the agencies overall effectiveness can be observed in other Member States such as Romania. While in Romania there has been a general improvement with regard to the cooperation with EASO, several issues (i.e. lack of access to education for asylum seekers) prove that there is still a big lack of effectiveness and operability on the part of the EU agency. Despite its willingness to overcome national deficiencies relating, for instance, to delays in the implementation of the EU legislative framework, the implementation of its action plans results in human rights violations and procedural shortcomings, as the cases of Greece and Romania reveal.

Lastly, the lack of funding and of technical assistance in reference to EASO’s missions make the realization of its prescribed mandate and mission difficult. From a financial and administrative perspective, many MS, such as Malta, report issues with funding, while others, such as Greece, emphasize on the lack of coordination with corresponding national agencies. Especially regarding the latter, issues of “intra-EU and international solidarity and responsibility sharing” are some of the most immediate challenges according to the Commission. Further, in terms of providing technical assistance and expertise, as has been reported, EASO may tackle the possible issues by “ensuring national experts and listing them in ‘asylum intervention pool’ with the aim of increasing the engagement of other MS”. However, this action remains insufficient, since the MS remain reluctant. This points to a lack of action at a central-governmental level. In this sense, even when, for example, EASO deploys its own officers to support and assist national authorities, they de facto “tent to outnumber the national experts”, undertaking “a substantial amount of work on their behalf” (Lisi and Eliantonio & Horii). Overall, the lack of adequate support—from EASO towards the MS and from the central European level towards the agency—deteriorates significantly the implementation progress of EASO’s agenda, translating to a de facto ineffective instrument (in terms of speed and efficiency).

Increasing EASO’s de jure operational power: a step-by-step approach

Let us now take a step-by-step approach towards improving EASO’s operation and work.

First, we argue for further increase in EASO’s power in relation to situations in individual MS via the creation of small and independent operational bases (‘asylum authorities’) in the countries that face most asylum- and migration-related issues, moving away from their purely executive function of the ‘support office’ and cutting the cord with the ministries. While some Member States may have already adopted a similar approach to this, there is a need of uniformity across all the Member States facing the biggest challenges related to migration. This would facilitate the process of cooperation between these Member States, when need may be, considering that they will have similar structures and frameworks for the same issues. Accordingly, the most important feature of these newly established ‘asylum authorities’ would be their power of being independent from the central governments of the MS.

Second, the next issue mentioned above could be addressed and solved by the MS through granting decisional and binding powers to EASO. EASO would be able to take immediate action on the territory of any MS, if the urgency of the matter demands this. Not only will the accountability issues diminish, but this may also be the only way in which EASO would become truly legitimate in the eyes of the normal EU citizen, showing its true potential in solving migration-related problems. Consequently, this potential can only be achieved by granting the necessary tools to a, so far, small and fragile agency. This solution could be reached if the Member States agree to give EASO the necessary competences to act, therefore by diminishing their sovereign power in this area in favor of the EU agency. This way it can be ensured that an accountable agency such as EASO can overstep State authorities without hesitation in emergency situations.

Last, EASO disposes of a very limited budget and a small number of staff members at its headquarters, making it even more dependent on the help offered by the MS themselves, on a regular basis. For most missions and operations, MS send their own teams of experts in order to assist EASO, lending it their own representatives. The solution suggested is an increase by the EU for EASO’s budget, followed by an initiative to increase the agency’s size in terms of available resources and personnel. One way to achieve this solution would be to grant EASO access to the funds made available by the EU under the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF), which amounts to €9.882.