Today, our blog celebrates its 100th blog post. Since September 2016, we issue at least one blog post per month, always on the last day of the month. The blog is open to anyone wanting to contribute, also in a different language than English. Our aim is to create a central point for information, research and discussion on the pertinent issues related to the so far understudied theme of the enforcement of EU law. Until now, we have had blog posts, which would announce a new book, idea or project, discuss a recent court judgement or legislative proposal or act, give a comment on a publication or summary of a recent event, to name but a few of our topics. The form of the blog post is thus flexible and inclusive.

This special blog post presents a discussion on some of the pertinent questions that the editing team sees as important in their respective research fields and warrants our further attention and investigation. This post is thus also a call for future blog posts and other initiatives, which could support and enhance the main theme of the blog – ultimately, to aid legislative and enforcement practices (in the EU as well as other jurisdictions) and to promote beneficial policies for society. Ideas for blog posts and full texts could be sent directly to the editors, whose contact details are to be found in the right pane on this website.

But first of all, why blogging?

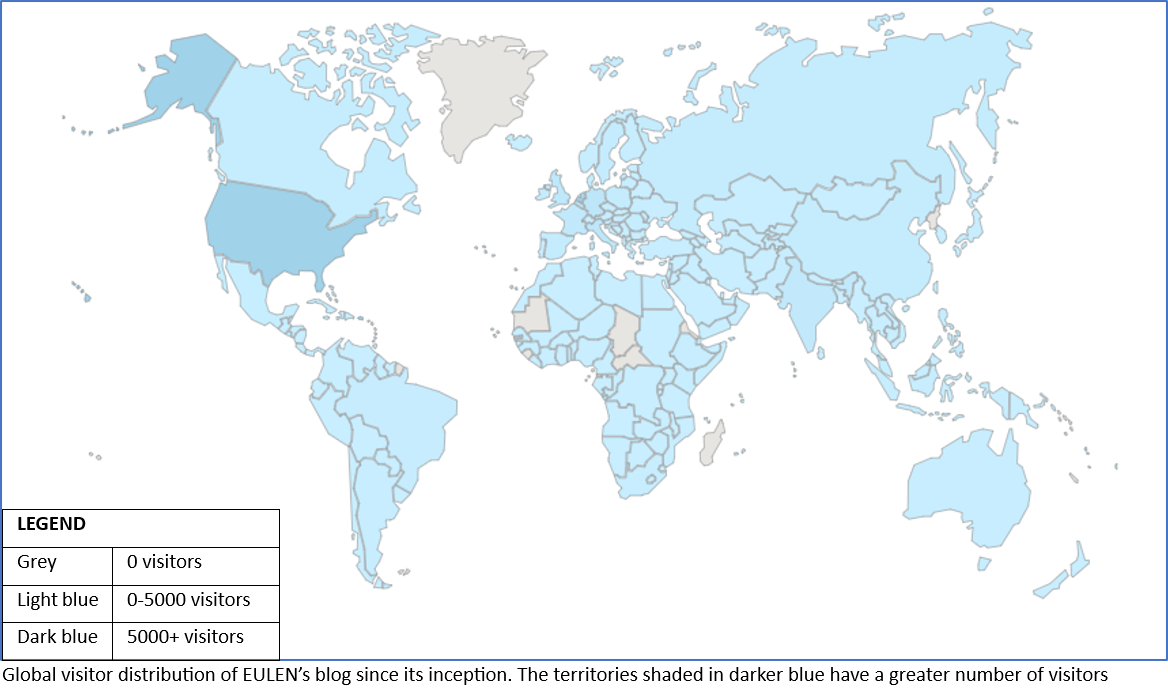

Since its inception, the posts in this blog have attracted over half a million viewers from 173 countries, which is a testament to its usefulness and steady readership over the years. The blog has visitors from all continents as depicted in the image above and we trust we can further enhance our readership by blogging about issues related to enforcement broadly, including in a developmental context. Hence, we welcome such contributions and remain committed to the blog form as a short and effective medium to communicate ideas. To illustrate this belief, we give you at least three reasons to blog:

-

- Spread ideas and findings;

- Experiment with flexible format for writing;

- Formulate your message succinctly.

Firstly, blogging can help you in distributing your (research) findings. In this way, you can reach more academics, if that is your target group, and you can contribute to society and practice. Thanks to our longstanding tradition and exceptional regularity, we have become the key discussion forum on the issues of EU law enforcement. The word expectation of about 1000 words also serves this function as it allows readers to learn about your message in a short period of time…and lack of time is an issue that we all share.

Secondly, it gives you a possibility to write in a free format and on a different topic than you may normally read about. A blog post can take a flexible format – it adds to the existing formats of a book review, academic article, official reports, etc. and it gives you an opportunity to experiment with new fields. Furthermore, the topics can vary. You can write a book or court judgement review, you can give an overview of an upcoming or past event, including its conclusions. You can introduce your new ideas and announce relevant projects in novel ways, including sharing your data set.

Thirdly, the exercise of writing blog posts pushes you to think hard about the key message of your research or work, which, if combined with writing of a lengthy paper or report, can often promote the quality of the latter. This is because writing a short blog post requires you to distill the key problem of your research and formulate your position/finding on it.

Known Unknows or the questions that warrant our attention (from the viewpoint and research fields of the editors)

Kelly: Enforcement in the field of criminal law, as others, is a consistently changing area, and this has been the area of my research. We observe changes such as transnational crime, as well as transnational enforcement mechanisms. These issues transcend criminal law alone and require us to reach deeper into international law and shared domestic norms. The rise of cybercrimes is the perfect example of criminal acts that reach across borders and require states’ cooperation. They additionally highlight the importance of EU laws that identify, target, and seek to enforce laws that aim to protect the public good and safety.

However, while we focus on the rise of online and transnational crime, it is important to remember the ways in which our enforcement mechanisms are evolving in tandem. While we observe digital hacking or dark web operations for instance, we are also provided with new ways to enforce criminal law. Our ability to track crimes and monitor public safety have been enhanced in innumerable ways in the past decade alone. The tools at our disposal for criminal law enforcement have become a powerful source of protection for public safety. It is a safe assumption to state that we all benefit from this evolution.

It merits mention, however, that these tools may also require their own enforcement and oversight. Just as technology increases the ability for crimes as well as its prevention, it may also contribute to abuses against human and fundamental rights. One of our first images of criminal law enforcement may be that of police surveillance or the overuse of power that comes as an occasional reality. Therefore, criminal law enforcement also entails the enforcement of other rights and privileges that act to mirror its enactment. Looking to EU Directives, such as the Law Enforcement Directive, or other privacy and data protection regulations (GDPR), as well as the AI Act, it is important to remember the aim of criminal law enforcement – the protection of the populace. When we consider these areas of enforcement as complimentary, we become closer to the goals of our legislators from the initial inception of law.

Zlatina: Moving to enforcement in the fields of competition law and utility regulation, the idea ‘novel challenges call for novel enforcement’ is becoming increasingly prominent given the various crises that the world is now facing.

Starting with competition law, authorities on both sides of the Atlantic are currently questioning old enforcement goals and paradigms, triggered by the power of the so-called ‘GAFAM’ behemoths. The laissez faire neoclassical economic logic pioneered by Bork and others in the 1970’s, which still informs enforcement, is ceding way to novel types of thinking on what constitutes the very core of the concept ‘competition’. In the US, neo-Brandeis thought is gaining ground, fueled by social unrest due to rising economic inequality. This movement is also supported by the appointment of its main proponent – Lina Khan – to the position of FTC Chair. However, it is yet to be seen how much of this ‘wind of change’ will become visible in, for instance, pending GAFAM-targeted enforcement decisions. Being less affected by the abovementioned developments, the EU has chosen a regulatory path to tackle digital giants – the Digital Markets Act has already bore its first enforcement fruits. However, commentators are not too pleased with several issues that are surfacing – to name but a few, competence division between the Commission and Member States seems to be problematic, as well as there being a significant overlap between DMA’s scope and competition law.

Regarding EU utilities regulation, current developments (such as the 2023 energy crisis) are calling for novel solutions and enforcement methods that keep EU energy prices internally steady even in times of external volatility. For instance, regulators could buy ‘affordability options’ from generators – ‘a form of insurance that would return profits from excessive prices to consumers.’ Additionally, the recent Draghi Report makes suggestions on how to keep prices low by capitalizing on sustainable energy production, the key to which is investment in grids to supply it. Draghi contends that ‘From a European perspective, rapidly increasing the deployment of interconnectors should be the focus’. However, future infrastructural deployment is dependent on the abovementioned push-and-pull between the competence of the Member States and the EU, which also plays out in EU energy regulation. In the future, much will depend on political will but also on finding correct enforcement instruments to procure that will.

Mira: I have been investigating and teaching the enforcement of EU law for the last 10 years. I have noticed a number of interesting developments that I and my colleagues from academia and practice have discussed and studied already (‘verticalisation’ of enforcement, agencification and enforcement in the EU, shared enforcement and the system of controls, the protection of fundamental rights and rationales behind choosing EU agency or network of national enforcers). These investigations and discussions, also by my students via their blog posts, have led, among others, to new questions that are crucial to answer to enhance our understanding of the enforcement of EU law and to offer solutions to many (legal) challenges.

For one, what should be the enforcement power of the EU and who should establish this – representative organs, the demos directly via the European Parliament and/or courts? This fundamental question is a pre-requisite to legitimizing all kinds of institutional innovations that we have seen in the past decades. At any rate, I believe that talking about enforcement issues up front, i.e. when making EU laws, is essential for effective policies and legitimacy.

Secondly, we badly need conceptual clarity on the essentials of enforcement and its successes or when it is effective. ‘Is enforcement a norm, effort, and/or result-orientated process?’ (as my colleagues Meyer and Tsilikis have written in their chapter in my recently edited volume). In other words, can we say we have successful enforcement if we have relevant laws in place, or do we count effectiveness by the ‘numbers’ – numbers of inspections, fines, etc.? Or is it about the result as such (being able to prove a violation which is then also upheld on appeal if the latter takes place)?

Finally, these issues need to be studied continuously to also build reliable statistics to gain more certainty as to what and when enforcement works and when and why it may not. Hence, empirical work on enforcement is equally needed.

Call for blog posts and other initiatives

We hope to have provided you with good food for thought and inspiration for your work in the field of enforcement of EU law. We invite you to share your findings, views, questions, data, etc., via your upcoming blog posts on this blog page.

- 100th Blog Post on EU Law Enforcement: pertinent questions that deserve our future research and societal attention. Call for Blog Posts (by Kelly Blount, Zlatina Georgieva and Miroslava Scholten) - October 31, 2024

- The Jean Monnet Network on enforcement of EU law (EULEN): results and conclusions - October 31, 2023