Blog post by Nicole, Thirza, Enes

As reiterated by President von der Leyen in her 2021 State of the Union speech: “The EU needs to ensure that every euro and every cent is spent for its proper purpose and in line with rule of law principles. EU funds are not allowed to seep away into dark channels”. If you have wondered which EU bodies are at the forefront of the protection of the Union’s financial interests (PIF) and how their cooperation works, you have come to the right place. In the almost two years the EPPO has been operational, the two Offices have had the first chance to interact and cooperate, as prescribed by their respective Regulations. In this blogpost, we outline the current updated EPPO and OLAF operational cooperation and its future possibilities to find out if teamwork can make the dream work.

PIF: A new player in the game

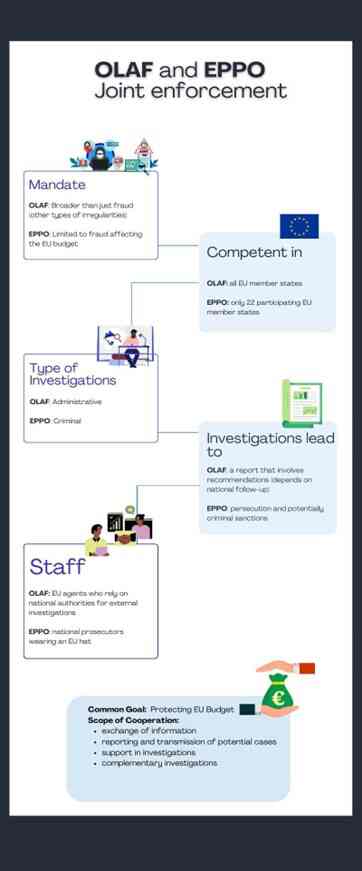

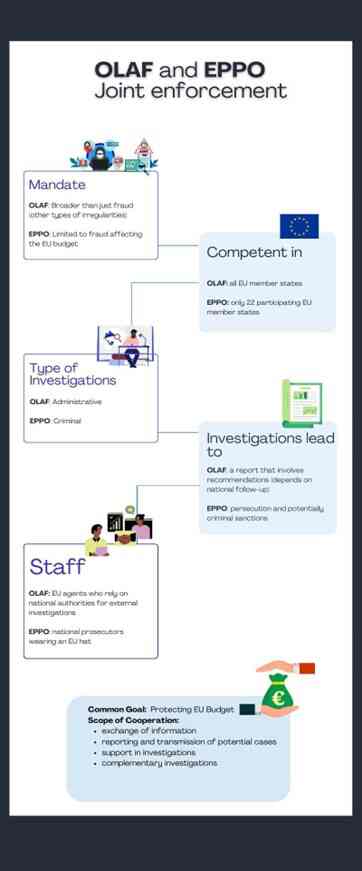

For more than 20 years, the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF), an administrative investigatory body with the mission to “detect, investigate and work towards stopping fraud involving European Union funds”, has been a preeminent actor in the PIF fight. However, in 2017 a new player entered the scene, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO). For the first time in EU history, an independent European body has the power to investigate and prosecute PIF crimes (see Figure A). As a result, we have two EU bodies with different sets of powers but with one common goal in mind: “to better protect EU taxpayers’ money and to bring all crimes against the EU budget to justice as quickly as possible.”

Figure A: Missions and Tasks of EPPO. Source: https://www.eppo.europa.eu/en/mission-and-tasks

OLAF and the EPPO in a nutshell

OLAF’s mandate encompasses investigation of fraud and corruption involving EU funds and serious misconduct within the European institutions as well as development of anti-fraud policy for the Commission. OLAF carries out both ‘internal’ or ‘external’ investigations, depending on whether or not they are conducted within institutions, bodies, offices and agencies of the EU (IBOAs). While conducting its investigations OLAF cannot exercise any coercive powers, so it has to rely on cooperation with national competent authorities. At the end of these investigations, OLAF cannot sanction the suspect or bring them to court. Instead, it can draw a report, binding on the IBOAs but not on national prosecutorial or judicial authorities of the Member States (MSs), and issue recommendations. In practice, the indictment rates following OLAF’s recommendations are low and vary significantly among MSs. That is because in some jurisdictions national prosecutors tend to prioritise the national aspects of cases, neglecting their European dimension, for instance, due to their lack of expertise.

In contrast, the EPPO has criminal powers through which it can investigate and also decide to bring a case to judgement before competent national courts until it has been finally adjudicated. Moreover, since the EPPO’s legal basis, Art. 86 TFEU, allows for the mechanism of enhanced cooperation, MSs could choose whether or not to join. Therefore, currently the EPPO counts only 22 “participating” MSs.

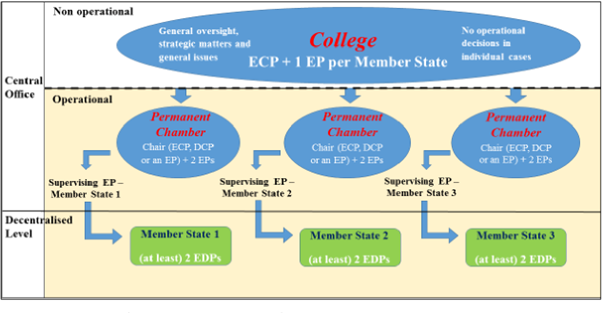

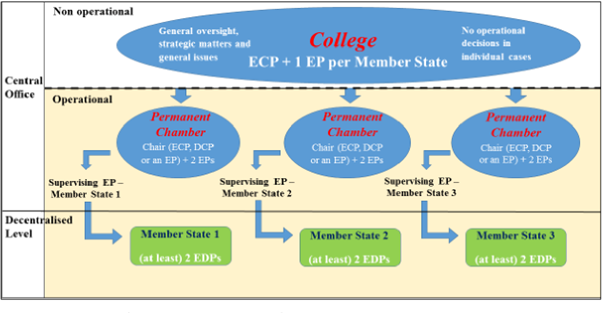

The implementation of these powers creates a complex legislative and organisational structure (here you can find a full explanation). Despite being a single office, the EPPO is composed of a central and a decentralised level, where different authorities play a role (see Figure B). As for the legal framework in which the EPPO operates, the EPPO Regulation provides only minimum rules, referring often to national laws especially in regards to its investigatory powers.

The EPPO and OLAF cooperation: ensuring no case goes undetected

The EPPO’s creation has definitely marked the transition into a new era for European enforcement in the area of PIF. However, in order for its potential to be fully exploited, the “new player” will have to play alongside its well-experienced team-mate OLAF. That’s why, expanding on the few ad hoc provisions contained in their respective Regulations, in 2021 OLAF and the EPPO further specified their obligations to cooperate by signing a Working Arrangement (WA). Considering this combined legal operational framework, let’s describe the most important aspects. First, in line with the principle of non duplication, OLAF needs to terminate its investigation if the EPPO is conducting one into the same facts. However, OLAF may support the EPPO in its investigations by means of operational, forensic, and analytical expertise and tools. Importantly, when providing this support, OLAF needs to respect the stricter criminal procedural safeguards contained in the EPPO Regulation. Additionally, under its own initiative or upon the EPPO request, OLAF can conduct parallel complementary investigations to address essential aspects of the protection of the EU’s financial interests, such as speedy recovery or the adoption of administrative precautionary measures.

|

Figure C: OLAF and EPPO Joint Enforcement

|

Moreover, the EPPO and OLAF can mutually exchange information, which enriches the capacities of both offices, enabling them to avoid duplicate investigations, and streamlining their operations. Additionally, the WA sets up a system for the reporting and transmission of potential cases. Since the mandates of OLAF and the EPPO do not fully overlap, this exchange is crucial to ensure that illicit activities detected by the EPPO in non-participating MSs do not escape OLAF’s investigation. Moreover, it guarantees that the EPPO is informed about any criminal offence falling under its mandate even when it was first detected by OLAF. In short, the exchange of both information and cases ensures that the EU’s resources are spent effectively and that every case is tackled by the appropriate authority.

Towards a joint enforcement mechanism?

A closer look at the envisioned OLAF and the EPPO cooperation supports the conclusion that the EU legislator aimed to create more than just two separate EU agencies. On the contrary, it seems that this could be the first step towards a comprehensive joint EU law enforcement system (see Figure C). Indeed, an integrated end-to-end cycle starting with OLAF investigations and ending with the EPPO indictments could be the future of the PIF enforcement in the EU.

Years of cooperation will be necessary to find out if teamwork will make this dream work or if it will remain but a distant dream. So far, it seems that both offices got off on the right foot and the EPPO 2022 annual report enthusiastically highlights the achieved results. Nonetheless, if a lasting relationship is to be built on these foundations, one must not forget that this increase in the powers of EU authorities should be accompanied by both guidance to and cooperation with national authorities and by appropriate guarantees for private individuals.