By Georgios, Maren & Julian

Significant banks can still cause severe dangers to the European financial market as shown by the SRBs first resolution case, Banco Popular. Banco Popular had severe liquidity issues which endangered the financial stability of Spain and Portugal. The swift resolution could have prevented a tremendous impact on the economy and possible costs of a state bail-out. The blog post aims to give an insight into how the SRB makes such a resolution decision looking at the Banco Popular case. Which shows that decisions made by the SRB are subject to democratic legitimacy concerns in the form of: judicial accountability, institutional balance and the amounts of discretion the Agency thereby.

Let’s talk about the development of the EBU and the SRB subsequent to the financial crisis

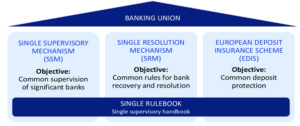

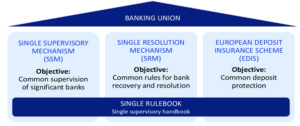

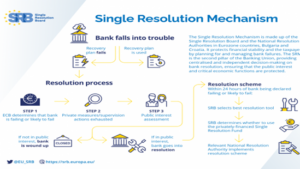

In response to the global financial crisis the EU created the SRB, an EU agency, to make the financial market more resilient and stable and to move towards the European Banking Union (EBU). This is one of the most significant developments in European Integration since the establishment of the Economic and Monetary Union; which was meant to restore confidence in the European banking systems after the double threat of the international financial crisis and the sovereign debt crisis. The EBU consists of 3 pillars: the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) and the European Deposit Insurance Scheme which is still under construction, as can be seen in Figure 1.

(Figure 1 – Banking Union)

The SRB is the EBUs resolution authority and therefore part of the SRM and has been established by the SRM Regulation (Regulation No 806/2014 (SRMR)). When a bank is failing or is likely to fail despite stronger supervision through the SSM, the SRM allows the effective resolution of the bank. The core mission of the SRB is to ensure an orderly resolution of failing banks, with minimum impact on the economy and public finances of EU countries, avoiding state bail-outs, which happened to a massive extent during the financial crisis to the detriment of the taxpayers.

The SRB as an EU agency has a broad mandate and an autonomous budget as independence is especially crucial when resolving significant banks. This mission is one of great societal relevance and one the author’s stand behind.

How does the SRB resolve a bank looking at the Banco Popular case

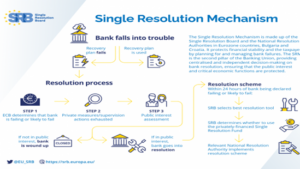

(Figure 2 – Resolution making process)

The procedure according to which the SRB adopts resolution schemes and according to which the resolution becomes a fully-fledged resolution plan, is described in Art. 18 SRMR. (Figure 2).

More specifically, in order for the SRB to draft a resolution scheme three conditions need to be fulfilled:

- Step1: Bank is failing or likely to fail

- Step 2: Private sector financing or any other private alternative does not exist

- Step 3: Public interest assessment

Step1: Bank is failing or likely to fail

First, the ECB should find a bank is failing or likely to fail, but it is also possible for the SRB to proceed to a similar assessment on its own. However, this only happens when the ECB is specifically requested by the SRB to make an assessment and when the ECB fails to act within three days of the request. In the case of Banco Popular the SRB initiated proceedings on the 3rd June 2017 and asked the ECB to assess Banco Populars situation. On the 6th June 2017 the ECB determined that the bank was failing or likely to fail as ‘[i]t is likely that the institution will not be able to pay back its debts or other liabilities in the near future’ (Art. 2). Thereby, the first condition of Article 18 (1)(a) is fulfilled, the bank is having severe liquidity issues endangering the financial stability of Spain and Portugal.

Step 2: Private sector financing or any other private alternative does not exist

Secondly, the SRB should assess that there is no reasonable prospect that any private sector financing, other private alternative or supervisory action could prevent the failure of the entity. The resolution, in other words, must be rendered as the most suitable and proportionate measure to avert the collapse of a certain bank. SRB in cooperation with the ECB determined that there is no reasonable prospect for private measures (Art. 3).

Step 3: Public interest assessment

Lastly, the adoption of the resolution must serve the public interest (Art. 18 (1), (5) SRMR). The SRB in cooperation with the ECB determined that the resolution is in the public interest to safeguard financial stability in Spain and Portugal (Art. 4).

In the Banco Popular case, the SRBs executive session, which consists of the Chair and four full-time members, which are observed by the Commission and the ECB, determined the three conditions given. Shortly after, it adopted the resolution scheme on the 7th June at 5:30 am according to Art. 18 (1) SRMR.

Thereafter, the Commission, within 24 hours of the transmission, could endorse or object to the resolution draft. If specific circumstances under the SRMR are given, within 12 hours of the transmission, the Council could be involved and asked to endorse or object to the draft within the next 12 hours. When the Commission remains silent and does not express any objections, the resolution enters into force automatically after 24 hours (Art. 18 (7) SRMR). If the draft is objected to, the SRB should reform the draft, incorporating the objections within the next 8 hours.

In the Banco Popular case, the Commission took 1 hour (5:30-6:30) to assess the decision and endorsed it. In a statement of reasons it stated: ‘[t]he Commission agrees with the resolution scheme[,] [i]n particular it agrees with the reasons of the SRB why it is necessary in the public interest’. This short time frame gives doubts to whether it just copy-pasted the decision or actually assessed it as required per the Art. 18 (7) SRMR and whether they sufficiently assessed the discretionary aspect of the scheme. Although the Commission is an observer in the entire process, it does not show how they assessed and evaluated each decision made by the SRB. Instead of merely saying ‘we agree’ some thorough reasoning why the Commission agrees is important to avoid future democratic legitimacy concerns in the SRB’s decision making process.

The SRB decided to use the sale of business tool (Figure 3), which enabled the conversion of capital into shares which were subsequently bought by Banco Santander for the symbolic amount of 1 Euro. Banco Santander was able to provide the necessary liquidity and Banco Popular was able to open the next day as a subsidiary of Banco Santander.

(Figure 3 – Resolution Tools)

The implementation of the adopted resolution relied solely on the relevant National Resolution Board. Nonetheless, according to Art. 29 SRMR, where a national resolution authority has not applied, not complied or has applied it in a way which poses a threat to any of the resolution objectives or the efficient implementation, the SRB may take over the implementation of the resolution, after informing the Authority and the Commission. In the Banco Popular case the Spanish authority swiftly implemented the SRB resolution scheme.

What democratic legitimacy challenges may arise from this process?

In our opinion it seems like the Banco Popular resolution has been successful in the way that it has prevented depositors of the bank and the taxpayer to lose money and safeguarded the financial stability in Spain and Portugal. However, despite the evident effectiveness of the resolution and the resolution-making process, legal and institutional challenges remain, which were also raised by the shareholders borning the burden of the bank’s rescue. The General Court rejected all of their claims in five separate cases. However, democratic legitimacy concerns persist to arise, also from certain aspects of the overall resolution making process provided in the SRMR as:

Firstly, even though it did not occur in Banco Popular, the SRB could come to the assessment that the three criteria are not fulfilled, thus no resolution decision would be concluded. As occurred in the ABLV case, whereto the ECJ decided that the SRB’s non-resolution decision could not be challenged (Ernests Bernis case). The action for annulment (Art. 263 TFEU) by the shareholders, on which the decision had an economic effect, was inadmissible due to the missing legal effect on them. This makes the non-resolution decision unchallengeable for the ones economically affected, questioning the legal accountability.

Secondly, the SRB’s resolution scheme can be automatically adopted, if the Commission remains silent for the 24 hours after transmission. Then the SRB exercises discretionary policy-making powers with questionable safeguard of accountability in place.

Thirdly, even when the SRB’s decisions are reviewed by the Commission or the Council, the short deadlines of 24 hours and 12 hours provided by the SRMR, could cause doubt to a thorough review. Creating concerns about the de facto integrity and actual facilitation of such a review process. The 77 minute long Commission’s review of the Banco Popular resolution scheme, indicates more of an approval of SRB’s decisions, without any real assessment. although it could be argued that the Commission is involved as an observer beforehand and therefore steers the SRB, using their final say as a negotiation tool. However, is this sufficient to quantify a thorough assessment.

These three questions relating to democratic legitimacy remain after looking at the Banco Popular ‘saga’ and the SRB’s resolution process.

Corruption scandal at the top of the EU

Corruption scandal at the top of the EU

The EPPO

The EPPO  The defendant (left) against the powerful EPPO (right)

The defendant (left) against the powerful EPPO (right)

©

© ©

© ©

© ©

©