By Andrea & Mathias

The new Commission proposal on CCP supervision aims to resolve some accountability issues. However, it also creates some. But the draft legislation is not beyond repair.

In June 2017, the Commission issued a proposal for a regulation to amend the EMIR and ESMA regulations in an attempt to improve the supervision of Central Counterparties (CCPs). CCPs are independent financial institutions that act as intermediaries between the buyer and seller of a security. While ESMA has considerable supervisory, regulatory and enforcement powers in relation to the derivatives market, authorisation and supervision of CCPs has primarily remained a Member State Competence.

The Commission outlined in the proposal their concern that supervision by National Competent Authorities (NCAs) gave rise to problems such as:

1.) Regulatory and Supervisory arbitrage caused by a lack of convergence of standards in Member States where the CCP is established; and

2.) National Competent Authorities in a single Member State is making decisions with appreciable cross-border implications concerning CCPs with an increased concentration of clearing services.

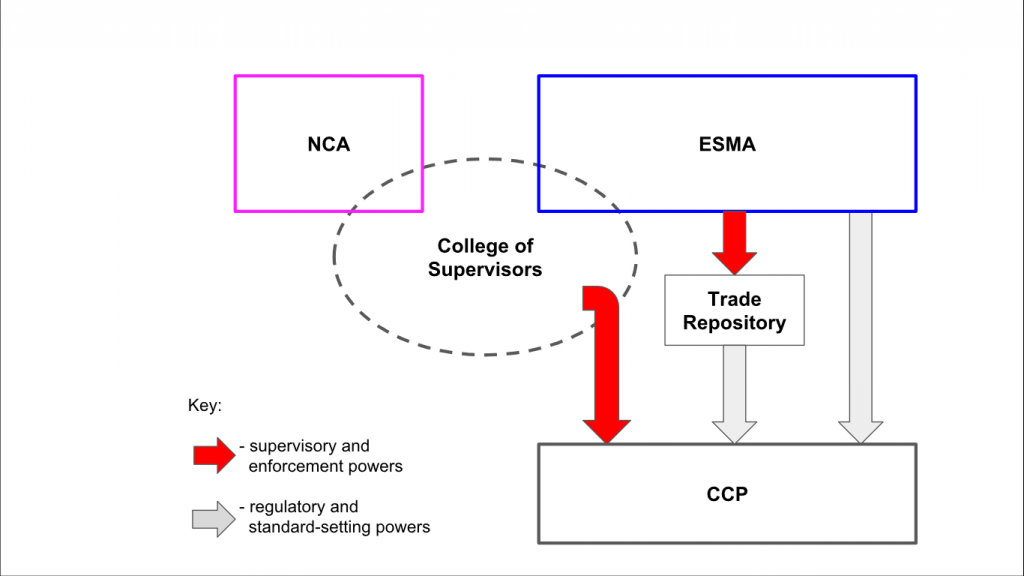

Current CCP supervisory framework

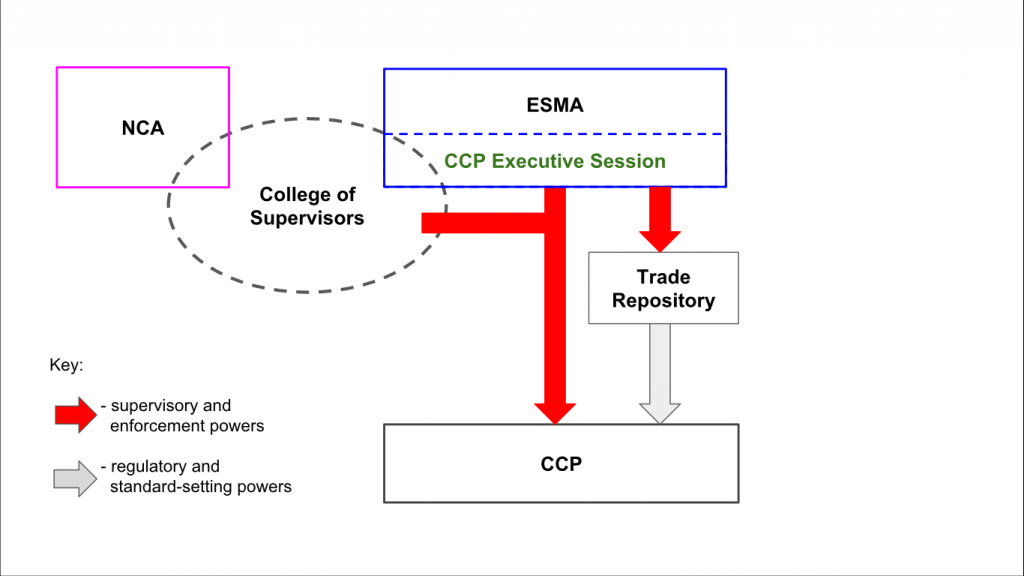

Proposed CCP supervisory framework

Shifting Competences

While the National Competent authority has primary competence in relation to CCP authorisation and supervision, it must involve the College of Supervisors on which there are representatives of ESMA as well as competent authorities from other Member States the CCP concerns. If the college votes against the authorisation of a CCP by unanimity, the NCA cannot authorise it. If they vote against it by a two-thirds majority, the matter must be referred to ESMA who make a decision the NCA should adopt. ESMA have no voting rights on the College of Supervisors and is there primarily to ensure the consistent and coherent functioning of colleges throughout the Union. The current supervisory structure is represented in the diagram.

The proposal makes a few important changes to the division of National Competences and ESMA. It provides for the establishment of the CCP Executive Session (‘the Session’), a component of ESMA that is both independent from and accountable to the Board of Supervisors of ESMA. The Session has four voting members, the Head, two directors and the representative of the relevant NCA, the head having the casting vote. Under the proposal decisions that can currently be made by the NCA will require consent from the Session. A few examples include decisions relating to access to a CCP, authorisation and withdrawal of authorisation of CCPs and review and evaluation of CCPs. Furthermore, under the proposal, the Head and directors of the Session would replace the current ESMA representatives on the College of Supervisors and in addition, would gain the right to vote on an opinion of the College. While the NCA is currently exclusively in charge of reviewing CCPs compliance with ESMA and can itself determine the depth and frequency of supervision, these competences will be shifted to ESMA who will also be invited to partake in on-site inspection. Clearly the proposal thus shifts primary supervisory roles from the NCA to ESMA.

Shifting Accountability?

An increase in competences for a public authority should go hand in hand with mechanisms that hold it accountable. As ESMA currently already wields supervisory power over Credit Rating Agencies and Trade Repositories, there are such mechanisms that would also apply in the case of CCP supervision. Yet, the question may be raised whether the current accountability mechanisms are sufficient in the new setting.

In line with Bovens’ definition, political accountability achieved when three criteria are fulfilled. An actor needs to be (1) required to explain and justify its actions before its forum. There must be a (2) possibility for the forum to interrogate the actor and the forum may (3) pass judgement on the conduct of the actor.

In line with Bovens’ definition, political accountability achieved when three criteria are fulfilled. An actor needs to be (1) required to explain and justify its actions before its forum. There must be a (2) possibility for the forum to interrogate the actor and the forum may (3) pass judgement on the conduct of the actor.

1.) With regards to explanation and justification, the Executive Director of ESMA has to include in ESMA’s annual work programme the activities carried out by the Session after obtaining its consent on any matters falling under its competences. The Executive Director must, also with the Session’s consent, prepare a multi-annual work programme. The Session has reporting duties towards the Board of Supervisors.

2.) The European Parliament and the Council may interrogate the Head of the Session whenever they desire. The Head of the Session shall report to Parliament in writing on the Session’s activities, if requested also on an ad-hoc basis.

3.) Parliament or the Council may inform the Commission that they believe that the Head and/or a Director of the Session should be removed from office. In case of serious misconduct, on a proposal from the Commission that has been approved by Parliament, the Council may decide to remove the Head of the Session and/or a Director from office.

To provide judicial accountability, CCPs will have the right to appeal ESMA’s decisions before the Board of Appeal. This body acts as the independent and impartial Board of Appeal of the European Supervisory Authorities. Decisions made by the Board are binding on ESMA and can be reviewed by the CJEU. In certain jurisdictions, national courts maintain the right to hold ESMA accountable for arbitrary decisions.

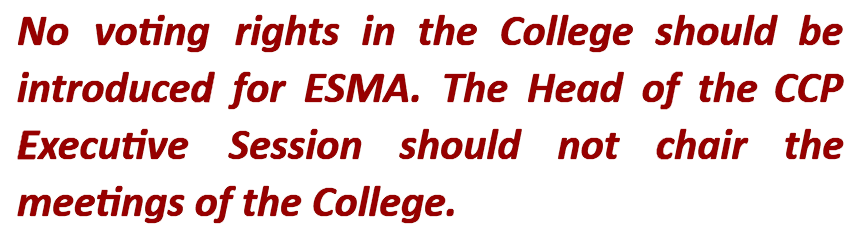

We see no gaps in the judicial accountability within the proposed framework but there are shortcomings with regards to political accountability. Having the members of the Session as voting members on the College provides for a duplication of roles and raises concerns regarding the determination of accountability for decisions taken. Therefore, we suggest that no voting rights in the College are introduced for ESMA. Furthermore, the Head of the Session should not chair the meetings of the College. We believe that this will maintain the separation of competences.

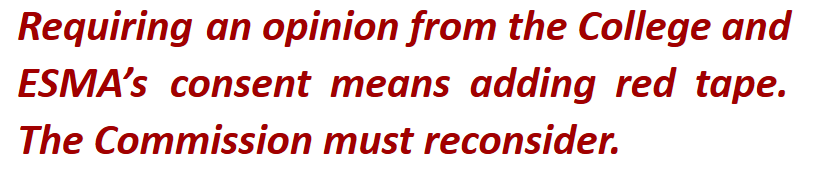

A problem still remains: The requirement of a further decision by the Executive Session extends the decision-making process by 15 calendar days and is contrary to the Commission’s stated objective of streamlining the decision making process. This was a concern for respondents to the proposal such as the London Stock Exchange Group. The Commission therefore needs to reevaluate its proposal focusing on situations where both an opinion from the College and ESMA’s consent are required.