By Katelijn, Kyriaki, Nik & Tim

Introduction

The Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) ruling in the case C-281-22 (Parquet Européen) has been hailed as a legal triumph by the European Public Prosecutor’s Office (EPPO). Initially perceived as a validation of EPPO’s strategies for streamlining cross-border investigations, the decision was met with celebration. However, upon closer assessment of the facts of the case and questions posed of the EPPO’s jurisdictional reach, it becomes clear that the legal complexities surrounding the case are extensive. The Court’s final decision rested on their emphasis on mutual recognition when interpreting Article 31 and 32 of the EPPO Regulation. This revealed the Member States obligation to adhere to a balancing test between efficiency and fundamental right protection. The decision marks an important step in the future of transnational crime prosecution. Given that the case forced the CJEU to explain and clarify EPPO’s scope under European law, this blog aims to provide the much-needed analysis of its rationale and implications.

Assessing EPPO’s reach in Parquet Européen: cross-border customs fraud

Parquet Europeén case gave the CJEU the first opportunity to provide a judicial review of the jurisdictional and institutional frameworks of the EPPO. The case concerned an individual that was involved in cross-border criminal activity that was against the interests of the EU budget, which is the legal basis for action under the EPPO’s competence. G.K. and S.L., who are individuals and managing directors of B.O.D. GmbH, were prosecuted for importing biodiesel fuel into the European Union using false customs declarations with intent to avoid the levies and, therefore, causing EUR 1,295,000 in damages.

The Austrian European Delegated Prosecutor (assisting EDP) sought judicial authorization for searches and seizures at both the business premises of the companies involved and the personal residences of G.K. and S.L. in Austria. This investigation measure was provided by the German (handling) EDP who opened the investigation and required assistance from the Austrian EDP. EDPs are authorized representatives of the EPPO within every Member State that participates in the supranational framework. They are authorized to order searches, seizures, arrests and are an important institutional element within the decentralized EPPO structure. The measures ordered by the German EDP were executed in Austria and, following appeals from G.K. and S.L., ended up on the CJEU’s desk for a preliminary ruling. The Court was tasked with interpreting Articles 31 (cross-border investigations) and 32 (enforcement) of the EPPO Regulation to clarify the scope of which material aspects of the investigative measure should be examined and by which EDP.

An emphasis on Mutual Recognition and Mutual Trust

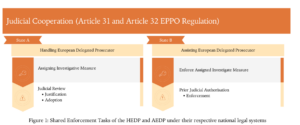

The Court of Justice expressed that, when interpreting Article 31 and Article 32 of the EPPO Regulation, consideration must be made to shared enforcement through judicial cooperation, i.e. Mutual Trust and Mutual Recognition. Mutual Recognition implies that one Member State has to ‘trust’ and accept that the other Member State has implemented the judicial decision within the scope of their national law without needing to check its legality while also acknowledging the differences in national law implementation. A State may only check when there is evidence or a strong suspicion of a serious risk of a fundamental right violation. The Court of Justice highlighted this through examples from the European Arrest Warrant and the European Investigation Order. They highlight this through the division of tasks and enforcement powers between the issuing and executing judicial authorities.

A closer inspection of Article 31 and Article 32 of the EPPO Regulation specifies where and how the tasks assigned to the competent authorities of the handling EDP and the assisting EDP should work according to their own national criminal law systems. The former is responsible for assigning the investigative measure and to provide a prior judicial review of their justification for adopting such a measure. The latter is only responsible for providing a judicial review based on judicial authorization on the enforcement of the assigned measure.

Has the Court made any sacrifice in the altar of the efficiency?

The Court was clear: to have an efficient mechanism of cross-border investigations, in other words easier investigation and prosecution, the right way is to opt for the division of tasks regarding judicial authorization. The EPPO welcomed this approach, as it was also in accordance with the prior decision of its College.

There is no choice but to wonder whether this efficiency comes at a cost to the protection of fundamental rights. After all, a strong argument in favor of the full judicial review by the Member State of the assisting EDP, is the need to ensure the effective protection of fundamental rights. According to AG, the Regulation contains sufficient safeguards in Article 41 (1) and (2). However, the Court’s decision to limit the obligation for a prior judicial review in the Member State of the handling EDP, to the cases where the investigative measures interfere only seriously with fundamental rights, raises concerns regarding the sufficient protection of the person concerned in the case that this serious interference does not exist. This is because on the one hand the meaning of the ‘serious interference’ is not defined, which gives some discretion to the Member States, and on the other, it seems that when there is not this serious interference, and the Member State decides not to provide for a prior judicial review, the person concerned does not have another option, an ‘escape shelter’, to ask for a judicial review in the Member State of the assisting EDP. The fact that the system described in the EPPO Regulation does not provide for refusal grounds regarding the assigned measure makes this concern more intense. Finally, the fact that the EPPO is based on a decentralized system, makes the issue of fundamental rights protection more of an obligation for national law to uphold. However, given the inherent differences between the Member States, it becomes extremely challenging to ensure the right balance between the EU enforcement rules with the effective protection of fundamental rights.

- [DRAFT] Frontex’s duties and refugees’ rights: an effectiveness vs. legality example at the EU borders. - April 11, 2024

- [DRAFT]EPPO in its first test before the CJEU: Case C-281/22 G.K. and Others (Parquet Européen) - April 11, 2024

- The Fundamental Rights Officer: Just what the EUAA needed - April 11, 2024