By Jaime, Jasper and Héloïse

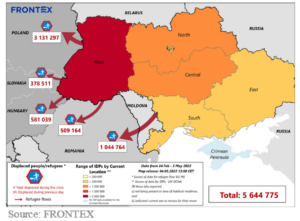

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine in February 2022, more than 6 million Ukrainian refugees have fled their home country, with the majority seeking refuge in the European Union; a number that can increase as the war rages on. Normally, Member States (MSs) and FRONTEX work together and cooperate to handle border control in the European integrated border management framework[1]. However, the gravity of the Ukrainian situation (the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees going as far as to qualify it as ‘the fastest growing refugee crisis in Europe since World War II) has incentivized an EU-wide response. Consequentially, the Council, after a Commission proposal, activated the old Temporary Protection Directive (TPD) Directive 2001/55/EC. This is an extraordinary instrument for situations of large-scale influxes that pose risks, especially when the standard asylum system is overwhelmed by the demand caused by the arrivals of displaced persons.

At its center, Frontex’s role enters a new work dynamic that might lead it to struggles with legality and effectiveness in its duties. Therefore, how does this unique geopolitical and legal situation affect Frontex’s duties, refugees’ rights and the border control process, on top of the already established asylum system?

Frontex, what do you work for and through which means?

Frontex stands as the European Agency in charge of ensuring European integrated border management at the external borders (Art.1, Regulation 2019/1896). We will not discuss its legal mandate in depth; rather, we will describe its goals and actions to achieve them.

Put in a general way, FRONTEX aims at managing EU borders efficiently in full compliance with fundamental rights and increasing the efficiency of the Union return policy. In other words, it supports EU Member States and Schengen Associated Countries in the management of the EU’s external borders and the fight against cross-border crime. This translates more specifically into sub-objectives:

- Work as an expertise center with the knowledge and skills to carry out the sector’s activities with high ethical standards.

- Fight cross-border crime, human trafficking and people smuggling.

- Monitor and protect borders (as part of the assistance of national authorities in border checks); also, monitoring migratory flows.

- Cooperate at the International and EU levels.

- Ensure a safer Schengen space and smoother travel (ETIAS).

As for the multitude of tasks that FRONTEX carries out, we can highlight:

- Border surveillance and coast guard functions.

- Detection of document and identity fraud.

- Research and Innovation.

- Training.

- Return and reintegration.

- Risk analysis.

These goals and actions may sound straightforward, but in the complex reality that we call life, they encounter the human aspect of the border panorama. Such a dichotomy pushes the enforcers at FRONTEX to make choices, sometimes sacrificing the effectiveness of their duties in favour of a more humane or simpler and faster process choice. However, before we delve into that aspect, let’s quickly understand the other side of the coin: the Ukrainian refugees and their rights.

Temporary Protection Directive, what do you bring to the refugees coming from Ukraine?

The Ukrainian situation did not change the normal procedure and rights that asylum seekers enjoy when approaching an EU MSs’ border. However, as mentioned, it did activate the 2001 Directive for Temporary Protection (TPD) through the Council implementing Decision 2022/382.

This piece of legislation covers Ukrainian nationals residing in Ukraine who have been displaced on or after 24 February 2022 and their family members, as well as Stateless persons and nationals of third countries other than Ukraine who benefitted from international protection or equivalent national protection in Ukraine.

Under the Common European Asylum System, asylum seekers are obviously covered by general international pacts and conventions (the Geneva Convention on Refugees, which states that every refugee has a right to protection; the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union). However, the TPD eases the process by granting the aforementioned refugees the following rights:

To all intents and purposes, it is, saving the distances of such basic comparison, a temporary EU citizenship pass that is almost free -for obvious reasons- of bureaucratic formalities. Furthermore, if any issues arise with the identification of a refugee who applies for the TPD, it would not translate into an automatic rejection since they will be directed to the regular asylum procedure. Sounds like a solid cover for the refugees. Nevertheless, we will take a sneak peek at how the system is working and how FRONTEX is faring so far.

On how race gets entangled with dichotomies.

As an example of effectiveness vs. legality, FRONTEX has proven that not everything is black and white when enforcing legislation at borders, especially in crisis situations. This is not, however, a critique of how FRONTEX’s performance, but rather an example of one task and objective (border control and detection of documents to ensure a safer Schengen) taking preference over refugees’ newly obtained rights.

Following this trend, some reports in May 2022 and June 2023 coincidentally refer to the differential treatment of refugees coming from Ukraine based on their race. To begin with, in 2022, due to the scale of the crisis, certain tasks in the countries that FRONTEX is supporting (for example, Romania and Moldova), mixed in nature.

As expressed by the Greek Minister of Migration and Asylum, Notis Mitarachi (right), in a public meeting with the Frontex Executive Director, 'Frontex is a security force not a welcoming committee'. Source: ASILE project.

Cracks in the system are noticeable: on one side, the TPD doesn’t cover nationals of other third countries and stateless persons without a valid permanent residence permit in Ukraine. It also leaves the interpretation of ‘family members of the refugees’ as a broad matter, up to the MSs to decide on it. On the other hand, MSs may extend the scope of protection to other categories of persons fleeing the war in Ukraine (Article 7(1) TPD) while the Commission asks MSs to ‘use their margin of appreciation in the most humanitarian way’. However, refugees from Ukraine (According to Human Rights Watch, sometimes people were prevented from boarding trains and buses based on their looks or race) who are not beneficiaries of temporary protection are being refused entry due to lack of the necessary documentation.

One must remember at this point that the choice of acceptance or refusal of safe passage into the EU remains in the hands of the MSs, not FRONTEX. Nevertheless, since FRONTEX acts in a supportive and cooperative manner for the most part, it is not unthinkable to understand that, as it has been reported, they have also proceeded to evaluate what a Ukrainian refugee under the TPD is and what is not; whether FRONTEX enforcers (along with the national ones) would prioritize strict and therefore safer Schengen exterior borders (the effectiveness), or they would soften the criteria and accept a greater number of people that, in the end, are trying to exit a war zone (the legality).

- [DRAFT] Frontex’s duties and refugees’ rights: an effectiveness vs. legality example at the EU borders. - April 11, 2024

- [DRAFT]EPPO in its first test before the CJEU: Case C-281/22 G.K. and Others (Parquet Européen) - April 11, 2024

- The Fundamental Rights Officer: Just what the EUAA needed - April 11, 2024