Over the past decade, no firm has faced more scrutiny for violating competition laws than Google. The avalanche of cases against the firm—over 100 around the world—is almost unprecedented. In that light, the question facing competition authorities is increasingly not whether Google has broken the law, but rather what to do about it.

Although consumers mostly experience Google through a platform like its search engine or maps product, it derives almost 80% of its revenues from its online advertising, where it is a dominant player. The AdTech industry is fundamental to how the internet is funded, with almost half of all websites showing ads. Yet the industry has long suffered from a lack of competition, and Google has faced allegations of anti-competitive behaviour in the sector.

In that regard, the European Commission has recently found the firm to have abused its dominant position by engaging in self-preferencing behaviour contravening Article 102 TFEU (similar investigations have been launched by the Competition and Markets Authority and the Canadian Competition Bureau). Having found the billions of euros of fines levied against the firm in previous cases to be an ineffective deterrent, the Commission has now proposed that Google divest itself of part of its AdTech business as to remove future incentives for self-preferencing. This blog post outlines an alternate approach, one which would have Google open up its ecosystem such that consumers could choose to fund their use of it through competing third-party advertising networks.

A different approach?

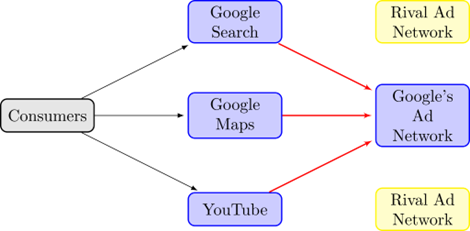

In a recent paper, Zlatina Georgieva and I argue that despite being on the more interventionist side of competition law, the Commission’s proposal still does not go far enough if effective competition is to be restored in the AdTech market. The key issue, in our view, lies in the Commission’s failure to address how Google leverages its dominance in other platform markets to consolidate power in the AdTech industry. A significant source of Google’s market power in AdTech arises not from its ability to compete on the merits, but rather from its ability to funnel huge amounts of internet traffic from its incredibly popular platforms—such as Google Search, YouTube, and Google Maps—into its own ad network. As long as these platforms remain dominant and are monetised through Google’s advertising network, the company will continue to wield substantial market power in AdTech.

One might think that such a situation is unavoidable—after all, advertising is vital to the functioning of zero-priced platforms such as Google Search. However, our concern is not with Google funding its platforms through ads, but rather with the lack of choice consumers have over who serves those ads. For instance, what if consumers like Google’s search engine, but prefer the more privacy-conscious advertising network of a rival? In other markets, consumers can mix and match service providers, such as by picking a mobile network to use with their smartphone. Following this logic, we ask: why can’t consumers choose which advertising network they want to use with Google’s free online platforms?

Marketised Monetisation

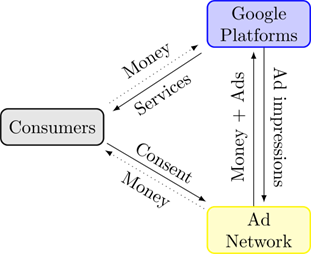

We envision a scenario where consumers are still able to consume Google’s products and services for free, but are monetised (i.e. advertised to) by a firm of their choice. This firm may be Google, as in the status quo, or it could be a third-party competitor which would compete with Google to attract customers to advertise to. This would work by Google charging a fee for its zero-priced services, but consumers delegating the payment of that fee to the advertising firm of their choice. Choosing an advertising network might then be like choosing a mobile network; something necessary to make online services work, but not tied into to the service itself. We call our remedy marketised monetisation, or marketisation for short, because it creates a consumer-facing market for the way in which platforms are monetised.

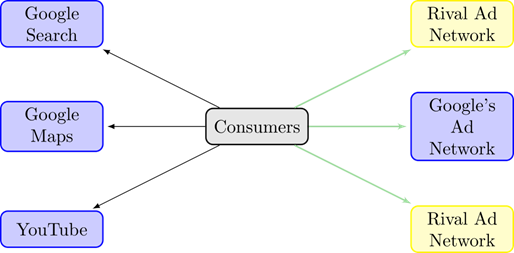

Marketisation would entail Google providing an open API which would allow consumers to ‘plug in’ a third-party advertising network into zero-priced Google’s platforms. The third-party firm would then monetise consumers by showing them advertising, and thus generating revenue. This is technically possible, not least because almost all the advertising-funded websites on the internet, such as recipe websites, already use third-party ad networks. The innovation we propose is to let the consumer choose which advertising network should be used, on dominant platforms like those of Google. If the Commission were to implement such a remedy, the market might instead look like this:

In the status quo, most consumers appear to prefer Google’s user-facing products, but it may not be the case that they also prefer its advertising network. Marketised monetisation would give them an independent choice of both. Accordingly, the remedy could open-up dimensions of competition that are currently bundled into consumers’ choices for which platform to use, thereby becoming more visible parts of the competitive offer. For instance, one could imagine consumers choosing which advertising network to use based on privacy, or on the relevance of ads. They could also choose to pay to see fewer ads, or use an ad network that shares part of the revenue it generates with its consumers and thereby receive monetary compensation. In the monopolised and stagnant duopoly that is the current online advertising market, such innovation is hard to imagine.

Implementing Marketised Monetisation – the enforcement aspect

In the paper, we consider how the above-described suggestion could be enforced as a remedy under EU competition law. Doing so under Article 102 TFEU would entail finding a theory of harm under which the remedy would be considered effective and proportionate. At first glance, a tying theory of harm would seem like a good option, which would frame Google as having made the use of its dominant platforms conditional on the use of its advertising network. Yet a tying approach would require the Commission to show that Google’s user-facing platforms and its advertising network are two distinct products, which may be difficult since consumers cannot choose an advertising network in the status quo.

Therefore, we conclude that the DMA is a more promising avenue for pursuing monetised marketisation as a competition remedy. Google is already designated as a gatekeeper with regards to the relevant platforms, and the purpose of the legislation is literally to foster contestability in digital markets. Yet we also note that the DMA is limited by narrow drafting, and observe that no provision in Article 5 or Article 6 DMA could achieve marketised monetisation as we envision it (although a combination of provisions could come close).

If it were to aim for an ambitious structural remedy like marketisation under the DMA, the Commission’s best bet might be to do so under Article 18, which allows for structural remedies in cases of systemic non-compliance with other obligations, or use Article 25 to create new obligations into the DMA which would give consumers a choice over which advertising network monetises them on Google’s platforms. This latter option would attempt to enact marketised monetisation through behavioural means (obligations under the DMA), which could eventually be escalated into a structural separation in the case of non-compliance.

Although we welcome efforts by competition authorities to investigate Google’s anti-competitive behaviour in the AdTech market, we are sceptical that the currently proposed remedies will be effective in the long run. We offer marketised monetisation as a remedy which could durably fix competition in the AdTech market. Admittedly, this remedy is one of the most interventionist strategies available to the Commission. However, if radical measures are essential but unachievable under current competition law, it may be time to consider a different approach, such as adopting a utility regulation framework as suggested by Cecilia Rikap, among others. While this topic falls beyond the scope of the current blog post and paper, it is a fruitful avenue for further research on digital (advertising) markets.

- Google AdTech – Break Up or Break Out? - January 31, 2025