By Riva, Fran, Birgit & Sanne

The European Banking Authority (EBA) is entrusted with safeguarding the integrity, efficiency and functioning of the European Union’s overall financial system, which includes combating money-laundering. Recently, the EBA has stepped up its enforcement actions in this area by investigating alleged breaches of the Anti-Money Laundering Directives more frequently. One of the powers that it has to address these breaches, is the breach of Union law (BUL) procedure. This procedure will be explored, giving two examples of when the EBA has used this power.

The breach of Union law procedure

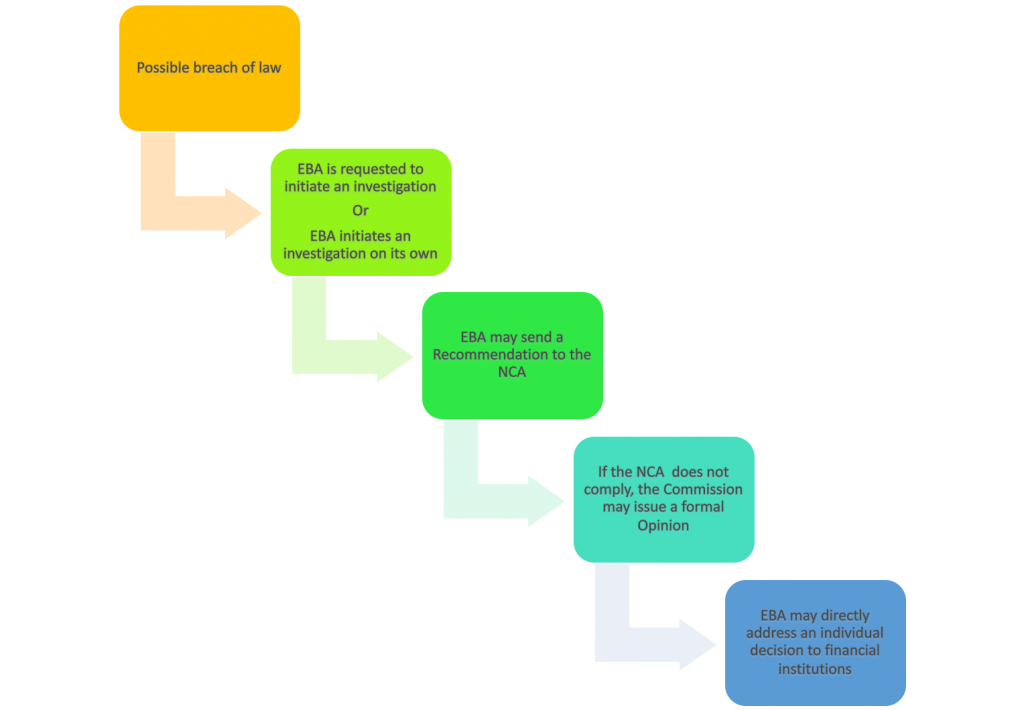

In the situation that a national competent authority (NCA) has not applied certain financial rules, has breached Union law in some way or has failed to ensure that a financial institution complies with the standards drafted by the EBA, the EBA may initiate a so-called ‘breach of Union law procedure’. Starting such procedure is one of the EBA’s enforcement powers. The EBA can investigate upon a request from one or more NCA, the European Parliament, the Council, the European Commission (EC), or the Banking Stakeholder Group. It can even begin an investigation on its own initiative, provided that it has informed the NCA that such investigation is being opened.

When an investigation is initiated, the NCA must, according to Article 17 of EBA’s founding Regulation 1093/2010, comply with and assist the investigation by providing the EBA with all relevant information. Subsequently, the EBA may send a Recommendation to the NCA, setting out the next steps to (re-)attain compliance with Union law. The NCA has one month to take action, and if the NCA still does not comply with the Recommendation and Union law, the Commission may step in and issue a formal Opinion, based on the EBA’s Recommendation. If the NCA still fails to comply, the EBA may directly address an individual decision to financial institutions in the NCA’s Member State (as well as to the NCA itself). The EBA outlines in its annual report which NCAs and institutions have not complied with Opinions or Decisions.

To see how the (BUL) procedure works in practice, let’s examine EBA’s recent investigation into a Dutch NCA, the DNB, initiated in November 2017. The EBA investigated the new DNB framework, as it was concerned that the DNB’s application of the definition of ‘local firm’ was incompatible with EU law. Subsequently, the DNB conducted an internal investigation, and amended its regime. The DNB concluded that its rules were sound, but that its definition of local firm was ‘legally untenable,’ and therefore chose to favour EU rules. Following the decision, the EBA closed its investigation.

Although the BUL procedure is an important enforcement power for the EBA to achieve its goal of harmonising the application of EU law, this procedure is used only rarely. Furthermore, there are several prerequisites for initiating a BUL investigation, and it seems the EBA settles most conflicts informally with the concerned NCA. A possible explanation for this could be that, once the EBA publicizes that it is investigating a breach of Union law, reputational damage is immediately inflicted upon that NCA. This is likely to have extreme impact on (for instance) public perceptions of its trustworthiness, and trust is essential to the credibility of supervisors.

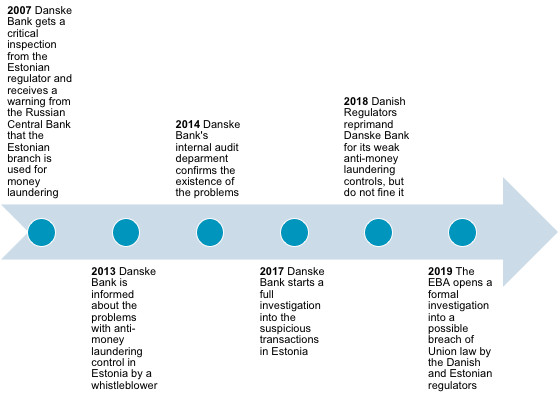

The Danske Bank Investigation

The Danske Bank money-laundering scandal has been called ‘one of the largest the world has ever seen.’ Over nine years, an estimated 200 billion euros of questionable funds flowed through Danske’s Estonian branch. In January 2019, following a letter from the EC, the EBA opened a BUL investigation into the Danish and Estonian financial services authorities. Danske Bank falls within the jurisdiction of the Danish competent authorities. Under the Anti-Money Laundering Directive, the Member State where an entity is established is responsible for supervising its application of Anti-Money Laundering/Counter Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) policies and procedures, meaning the Danish authorities are responsible for ensuring Danske’s AML/CFT policies are adequate, and uniformly applied, including in the Estonian branch. However, the Estonian authority is responsible for direct supervision of Danske’s Estonian branch and is thus the authority who actually supervises the Estonian branch, including for its application of AML/CFT measures.

It was essential that the two authorities cooperated, but because of the split-jurisdiction, the Danish authority was required to inform the Estonian authority of any issues that could affect the assessment of the Danske’s compliance with the AML/CFT rules. Both authorities had previously investigated Danske Bank, but sanctions were limited, and no adequate remedial actions were taken by either authority, which allowed the money laundering to continue for several years. The EC, therefore, requested that the EBA investigates 1) the thoroughness of the national authorities’ inspections, 2) whether sanctions were applied in an appropriate way, and 3) if either NCA failed to comply with their obligations under Union law.

BUL procedure and the countering of money laundering: what’s next?

Money laundering has become a hot topic for the EU, and the recent scandals, including Danske Bank or with the Maltese bank Pilatus, created pressure to act. As a consequence, the EC has proposed a new mandate which would give the EBA more powers to tackle money laundering and terrorist financing. The changes would, among other things, specifically entrust the EBA with the power to 1) collect more information from more sources, 2) request that NCAs investigate potential breaches (and expands this to include breaches of national law, transposing Directives or exercising options granted by EU law), and to 3) directly address decisions to individual financial sector operators other than the institutions that are already governed by the EBA and its rules. These new powers seem very promising, but there is a long road ahead until their efficacy can be assessed.

- [DRAFT] Frontex’s duties and refugees’ rights: an effectiveness vs. legality example at the EU borders. - April 11, 2024

- [DRAFT]EPPO in its first test before the CJEU: Case C-281/22 G.K. and Others (Parquet Européen) - April 11, 2024

- The Fundamental Rights Officer: Just what the EUAA needed - April 11, 2024