By Lauren, Florentina, Maria and Rei

Enforcing EU environmental law is essential in combatting climate change and protecting the environment. Yet, non-compliance with environmental law is the leading cause of the commencement of infringement actions every year. Since the start of this year alone, the Commission has opened 85 infringement actions against Member States (“MS”) for non-compliance with environmental law. Infringement actions are lengthy and costly. Given the shortcomings of ex post enforcement, the question arises of how environmental enforcement can be improved ex ante. This blog post looks at four ways in which the European Environment Agency (‘EEA’) can help to plug information gaps in environmental enforcement at the national level, thus potentially reducing infringement actions by the Commission and preventing environmental harm.

The EEA is an information-providing agency. Some of its roles listed in its founding regulation include

- Providing information needed for sound environmental policy to MS and the Commission (DG Environment, in particular);

- Ensuring that the public is properly informed about the state of the environment;

- Assisting the monitoring of environmental measures and recording and assessing data on the environment, ensuring that the data is comparable at a European level.

It has been argued that in the past the agency has acted as more of a ‘loyal lapdog’ to DG Environment, whereas it has the potential to act as more of a ‘barking watchdog’. Given its roles and powers assigned in its founding regulation, we argue that the EEA could improve enforcement of environmental law in the four following scenarios:

(1) First possibility: EEA information gathering on criminal law enforcement by MS

Inspections are crucial in preventing environmental harm. Blanc and Faure (2018) discuss current problems with environmental inspections in MS. The first one is that the Commission may only carry out an inspection on MS soil if the MS gives permission for the Commission to inspect. This problem arises with Directive 2008/99, which obliges MS to enforce criminal law for certain environmental crimes. For example, Article 3 of the Directive requires MS to criminalise the destruction of protected habitats and to criminalise the discharge of potentially deadly materials into the air, soil or water. However, once the Directive is transposed into national law, the MS may enforce the law in a weak manner. Faure (2017) gives the example of how this happened in the case of Sweden’s transposition of the Directive. The Swedish sanctions in place for corporate environmental crime were considered to be too low, and therefore not considered effective, proportionate and dissuasive.

The core enforcement problem with the Directive is that the Commission lacks information with respect to penalties imposed by MS. In particular, Blanc and Faure note that the Commission lacks information with regard to the capacity of environmental inspectorates and prosecutors, and on prosecutions and sanctions at the national level. A recommendation was made for the Commission to introduce legally binding minimum criteria and guidelines for inspections carried out by MS to ensure better enforcement of environmental law. This remained, however, a recommendation, as the Commission refused to make the minimum criteria and guidelines legally binding. This is where the EEA could step in, given that the agency already collects data from the national level to present at the EU level. The EEA manages the EIONET network, a forum whereby MS share environmental information and set common data reporting standards. One could imagine a scenario wherein MS report data on environmental criminal sanctions via this forum, with minimum reporting standards. However, a potential drawback for this is that the EEA has no powers to oblige MS to deliver up the necessary information.

(2)Second Possibility: The information-gathering role can be enhanced

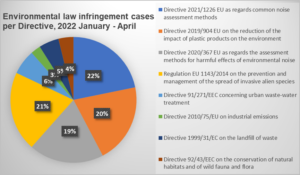

Figure 1: Infringement cases opened January 2022 – April 2022, per legislative instrument breach

When discussing which powers EEA has and which problems it encounters, the first thought that comes to mind is to give it more powers. However, this section investigates if the current powers that it has can solve, at least partially, the underenforcement problem.

As mentioned, a high number of infringement cases on environmental law exist. Adopting a qualitative legal research method, the main causes of these infringements will be investigated, based on which Directives are breached. Further, it will be assessed whether EEA, if given more powers, could have prevented, at least partially, these infringements from happening.

It was determined that from the beginning of 2022, more than 80% of infringements were with regard to four directives and three major problems: noise pollution, failure to prevent the spread of invasive alien species (IAS), and failure to comply with sustainability measures.

Almost 21% of infringement cases concern Regulation 1143/2014 on the spreading prevention of invasive alien species (IAS). It requires MS to manage the pathways by which IAS are introduced and spread. However, MS have failed to establish an action plan under the Regulation. Most of the infringements in this sector are due to a lack of knowledge. Since the EEA is an information-gathering agency, it could have informed the MS about all IAS, how to identify which IAS are dangerous and how to deal with them. The list in the regulation ‘accounts for just 3% of all IAS’. Thus, updated annexes by EEA to the Regulation can mitigate this problem and avoid future infringements.

Directive 2019/904 EU promotes circular approaches that give priority to sustainable products. Many MS failed to transpose this Directive by missing the deadline, leading to 20% of infringement cases. Why is there such a high number infringement cases? This Directive is addressed to market players who need to change their behavior. MS act more as ‘supervisors’. After a substantial scrutiny of all these cases and their context, it was identified that little time given to MS, and the lack of a clear strategy on how to switch to sustainable products are among the causes of non-compliance. Thus, if the EEA could have helped industry actors with an action plan on how to make this change, some infringement cases could have been prevented.

Either way, when such important legislative acts are enacted, governments and market players should be assisted by a European agency to make sure the legislative goal is attained. The first objective of the Lisbon Action Plan is to achieve effective transposition. The EEA has enough information and expertise to be able to assist Member States to comply with environmental law. Even though it is acknowledged that now, it may be difficult to give EEA supervisory or enforcement powers, if it could mitigate information asymmetry problems more efficiently, it would have already been a success.

(3) Third Possibility: Promoting the collection of timely information

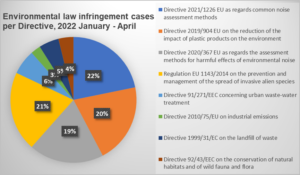

National authorities have not been able to sufficiently obtain timely information for effective enforcement. The following bar chart indicates the reporting performance of each country in EIONET in 2021.

Figure 2: Reporting Performance by each EU country in EIONET, 2021. Source: Eionet core data flows 2021

This chart indicates how often there was timely and high-quality data sharing from each country, with 100% being the best possible result. According to this chart, many countries achieved a high percentage in sharing timely data, however, in some countries such as Germany, the rate was only about 60%, a large gap compared to countries like Poland. This gap could generate a risk of ineffective enforcement in some countries because of insufficient timely information to address environmental challenges and this can affect the total quality of enforcement in the EU.

EEA can take measures to reduce the risk of the gap in some ways. One way is to improve the technical aspect of EIONET itself. This information portal site has an enormous amount of data, thus specific data may not be picked up immediately. The development of this database would increase the quality of information sharing to users. Also, the EEA can recommend authorities who have not offered much data compared to other countries to provide data regarding the enforcement situation of EU environmental law to EU institutions. This can put pressure on countries in cases where authorities in the EU have to address problems rapidly. Moreover, the process of sharing data can be improved. EIONET has an infrastructure called Reportnet, and it has a reporting process in 10 steps, but there are no limited periods in each step and this can lead to less timely information sharing. A new version developed in 2018 makes the process without external systems, but a specific period in each step should be also set.

(4) Fourth Possibility: Self-monitoring Scheme

Environmental competences are shared between MS and the EU. The EEA already has important information gathering powers. Objectives delegated to EEA could be enhanced by strengthening cooperation between the EEA and national environmental authorities.

It is possible to achieve the aforementioned target, by establishing a self-monitoring scheme. Based on this scheme, the EEA cooperates with national authorities for the purpose of monitoring compliance and gathering information regarding EU Environmental Law infringements. Main polluters of each MS by sector are obliged to provide information regarding compliance with EU environmental law to national authorities. The latter are responsible for referring this information to the EEA. Due to the fact that higher fines would not result in higher compliance, since companies would adjust their budgetary strategies accordingly, enterprises which cooperate would benefit with a reduction on the fine imposed for non-compliance.

By reducing fines imposed, enterprises would have a greater incentive not only to cooperate with the authorities and the Agency, but also to comply with EU environmental law. Consequently, the risk is reduced, considering that they bear certain rather than uncertain sanctions in case of non-compliance.

Through this Scheme it is not only enterprises who benefit, but the national authorities and the European Commission as well since it would result in saving enforcement resources. Those who report their harmful act, no longer require detection.

Such schemes already exist in many MS, though there is nothing as such at EU-level. Our proposal is for an obligatory self-monitoring scheme for main polluters at national level with a further obligation for national authorities to cooperate with the EEA.